William Morris Wallpaper Designs Biography

William Morris was born on March 24, 1834, at Elm House, Walthamstow. Walthamstow in those days was a village above the Lea Valley, on the edge of Epping forest, but comfortably close to Lonmdon. He was the third of nine children (and the oldest son) of William and Emma Shelton Morris. His famile was well-to-do, and during Morris's youth became increasingly wealthy: at twenty-one, Morris (quite ironically, given his later political views) came into an annual income of £900, quite a tidy sum in those days.

Morris's childhood was a happy one. He was spoiled by everyone, and was rather tempermental, as in fact he would be for the rest of his life: he would throw his dinner out of the window if he did not approve of the manner in which it had been prepared. He was smitten at a very early age, as many young gentlemen of his day were, with a great passion for all things mediaeval: at age four he began to read Sir Walter Scott's Waverley Novels, and he had finished them all by the time he was nine. His doting father presented him with a pony and a miniature suit of armor, and, in the character of a diminutive knight-errant, he went off on long quests into the depths of Epping Forest. He was rather a solitary child, close only to his sister Emma, and even in childhood was possessed of a romantic attachment to forests and gardens and flowers and birds which, with his interest in mediaevalism, would recur in his art, his poetry, and his fiction for the rest of his life.

Morris's family belonged to the Evangelical branch of the Church of England — they practiced what he would later refer to as a "rich establishmentarian Puritanism," which, even as a boy, he found distasteful.

In 1847, Morris's father died, and the following year, aged fourteen, he entered Marlborough College, where he did not learn a great deal, but where he came under the influence of the High Church Oxford Movement which had been inaugurated during the 1830's by Newman, Keble, and Pusey. After a riot occured at Marlborough in 1851 (it was rather a boisterous place), Morris left the school to continue his education at home.

In 1853 Morris, who had vague notions of becoming a High-Church Anglican clergyman, entered Exeter College at Oxford, where he met Edward Burne-Jones, who was engaged in similar pursuits: Burne-Jones, who would become one of the greatest of the Pre-Raphaelite artists, would remain Morris's closest friend for the remainder of his life. At Oxford Morris became a member of an undergraduate aesthetic circle which was enamored of an idealized Middle Ages and heavily under the influence of Tennyson's Arthurian poems, Carlyle's Past and Present, and Ruskin's The Stones of Venice. Again, these years were formative: Morris, already possessed by the feeling that he had been "born out of his due time," fell in love with mediaeval art and architecture and with the mediaeval ideals of chivalry and of the communal life. There too Morris began to write poetry which was heavily indebted to the work of Tennyson, Keats, Browning, and, most of all, his beloved Chaucer.

In 1855 Morris came of age and inherited the first installment of his annual income of £900. With Burne-Jones, he made a walking tour of the great Gothic cathedrals of Northern France. Both of them were overcome and decided to abandon their clerical studies in order to become artists, and Morris left Oxford at the end of the year.

In 1856 Morris began work (much to his family's chagrin) in the architectural office of G. E. Street, where he met Philip Webb, who would become another close friend and associate. He took rooms with Burne-Jones, already embarked on his career as an artist, in Red Lion Square, and before the end of the year Morris himself abandoned architecture for art. Burne-Jones had come under the influence of the older Dante Gabriel Rossetti, already the leader of the fledgling Pre-Raphaelite movement. Rossetti did not think very highly of Morris's work, but another youthful phenomenon, Charles Algernon Swinburne, himself an undergraduate at the time, encouraged Morris to consider having his poems published.

In 1857 Morris, Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and various friends painted the Oxford Union frescoes, now largely destroyed, and Morris met Jane Burden, one of Rossetti's models. In the midst of an uncomfortable courtship he continued to write poetry: The Defence of Guenevere appeared in 1858. Jane and Elizabeth Siddal were the Pre-Raphaelite ideals of beauty: Rossetti married Lizzie, and in 1859 Morris married Jane at Oxford. He was twenty-five, and she was eighteen. Both Jane and Lizzie came from working-class backgrounds, and both were traumatized by the fact that they had to play Galatea to the Pygmalions portrayed by their aristocratic young husbands. Lizzie committed suicide after two years after two years of marriage to Rossetti, and Morris's marriage was a very difficult one: Jane was moody and frequently ill, and within a few years of their marriage, playing Guenevere this time, had embarked upon a long affair with Rossetti, which permanently strained Morris's relationship not only with Jane herself but also with the man who had been first one of his heroes and then one of his closest friends. The first few years of their marriage, however, were relatively happy, and saw the birth of two daughters, Jenny and May. In 1860 Morris commissioned Philip Webb to designed Morris's famous Red House in South London: Morris and his friends and acquaintances decorated the house themselves in properly mediaeval fashion, building all the furnishings, designing stained glass windows, painting murals, and weaving tapestries, designing textiles, and discovered that they enjoyed it.

After Red House had been completed in 1861, the parties involved decided to found Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Company: other founder-members included Ford Madox Brown, Burne-Jones, Rossetti, and Webb. It was in 1861, too, that Morris began his long poem The Earthly Paradise.

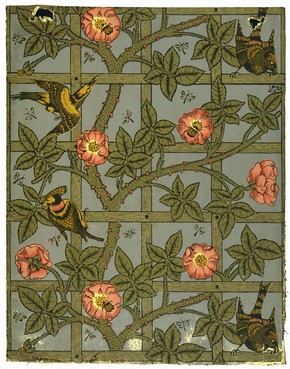

In 1862 Morris designed the first of many enormously influential wallpapers for the Company. By 1865 the affair between his wife and Rossetti was underway, and Morris, though he buried himself in his work with the firm, withdrew, in an emotional sense, into his poetry. The Life and Death of Jason, the themes and remoteness of which reflect his emotional isolation, appeared in 1867, and the four parts of The Earthly Paradise were published between 1868 and 1870. In 1868, too, Morris began to study Icelandic with Eirikr Magnusson, and in the following year, collaborating with Magnusson, he published his first translations from the Icelandic, The Saga of Gunnlaug Worm-tongue and The Story of Grettir the Strong.

1870 saw the publication of Morris's prose translation of the Volsunga Saga, The Story of the Volsungs. In the 1870s, too, Morris would make a new commitment — to increasingly radical political activity — which would dominate the rest of his life, though in some ways it was only an extension of his belief that things were not as they should be; a concerted attempt to resolve the enormous disparity between things as they were and as he believed they could and should be. For Morris, the Socialist movement, after 1870, came more and more to seem to be the only way to resolve the problems — poverty, unemployment, the death of art, the growing gap between the upper and lower Classes — which he saw as being the pervasive legacy, in Victorian society, of the ongoing Industrial Revolution.

William Morris was born on March 24, 1834, at Elm House, Walthamstow. Walthamstow in those days was a village above the Lea Valley, on the edge of Epping forest, but comfortably close to Lonmdon. He was the third of nine children (and the oldest son) of William and Emma Shelton Morris. His famile was well-to-do, and during Morris's youth became increasingly wealthy: at twenty-one, Morris (quite ironically, given his later political views) came into an annual income of £900, quite a tidy sum in those days.

Morris's childhood was a happy one. He was spoiled by everyone, and was rather tempermental, as in fact he would be for the rest of his life: he would throw his dinner out of the window if he did not approve of the manner in which it had been prepared. He was smitten at a very early age, as many young gentlemen of his day were, with a great passion for all things mediaeval: at age four he began to read Sir Walter Scott's Waverley Novels, and he had finished them all by the time he was nine. His doting father presented him with a pony and a miniature suit of armor, and, in the character of a diminutive knight-errant, he went off on long quests into the depths of Epping Forest. He was rather a solitary child, close only to his sister Emma, and even in childhood was possessed of a romantic attachment to forests and gardens and flowers and birds which, with his interest in mediaevalism, would recur in his art, his poetry, and his fiction for the rest of his life.

Morris's family belonged to the Evangelical branch of the Church of England — they practiced what he would later refer to as a "rich establishmentarian Puritanism," which, even as a boy, he found distasteful.

In 1847, Morris's father died, and the following year, aged fourteen, he entered Marlborough College, where he did not learn a great deal, but where he came under the influence of the High Church Oxford Movement which had been inaugurated during the 1830's by Newman, Keble, and Pusey. After a riot occured at Marlborough in 1851 (it was rather a boisterous place), Morris left the school to continue his education at home.

In 1853 Morris, who had vague notions of becoming a High-Church Anglican clergyman, entered Exeter College at Oxford, where he met Edward Burne-Jones, who was engaged in similar pursuits: Burne-Jones, who would become one of the greatest of the Pre-Raphaelite artists, would remain Morris's closest friend for the remainder of his life. At Oxford Morris became a member of an undergraduate aesthetic circle which was enamored of an idealized Middle Ages and heavily under the influence of Tennyson's Arthurian poems, Carlyle's Past and Present, and Ruskin's The Stones of Venice. Again, these years were formative: Morris, already possessed by the feeling that he had been "born out of his due time," fell in love with mediaeval art and architecture and with the mediaeval ideals of chivalry and of the communal life. There too Morris began to write poetry which was heavily indebted to the work of Tennyson, Keats, Browning, and, most of all, his beloved Chaucer.

In 1855 Morris came of age and inherited the first installment of his annual income of £900. With Burne-Jones, he made a walking tour of the great Gothic cathedrals of Northern France. Both of them were overcome and decided to abandon their clerical studies in order to become artists, and Morris left Oxford at the end of the year.

In 1856 Morris began work (much to his family's chagrin) in the architectural office of G. E. Street, where he met Philip Webb, who would become another close friend and associate. He took rooms with Burne-Jones, already embarked on his career as an artist, in Red Lion Square, and before the end of the year Morris himself abandoned architecture for art. Burne-Jones had come under the influence of the older Dante Gabriel Rossetti, already the leader of the fledgling Pre-Raphaelite movement. Rossetti did not think very highly of Morris's work, but another youthful phenomenon, Charles Algernon Swinburne, himself an undergraduate at the time, encouraged Morris to consider having his poems published.

In 1857 Morris, Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and various friends painted the Oxford Union frescoes, now largely destroyed, and Morris met Jane Burden, one of Rossetti's models. In the midst of an uncomfortable courtship he continued to write poetry: The Defence of Guenevere appeared in 1858. Jane and Elizabeth Siddal were the Pre-Raphaelite ideals of beauty: Rossetti married Lizzie, and in 1859 Morris married Jane at Oxford. He was twenty-five, and she was eighteen. Both Jane and Lizzie came from working-class backgrounds, and both were traumatized by the fact that they had to play Galatea to the Pygmalions portrayed by their aristocratic young husbands. Lizzie committed suicide after two years after two years of marriage to Rossetti, and Morris's marriage was a very difficult one: Jane was moody and frequently ill, and within a few years of their marriage, playing Guenevere this time, had embarked upon a long affair with Rossetti, which permanently strained Morris's relationship not only with Jane herself but also with the man who had been first one of his heroes and then one of his closest friends. The first few years of their marriage, however, were relatively happy, and saw the birth of two daughters, Jenny and May. In 1860 Morris commissioned Philip Webb to designed Morris's famous Red House in South London: Morris and his friends and acquaintances decorated the house themselves in properly mediaeval fashion, building all the furnishings, designing stained glass windows, painting murals, and weaving tapestries, designing textiles, and discovered that they enjoyed it.

After Red House had been completed in 1861, the parties involved decided to found Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Company: other founder-members included Ford Madox Brown, Burne-Jones, Rossetti, and Webb. It was in 1861, too, that Morris began his long poem The Earthly Paradise.

In 1862 Morris designed the first of many enormously influential wallpapers for the Company. By 1865 the affair between his wife and Rossetti was underway, and Morris, though he buried himself in his work with the firm, withdrew, in an emotional sense, into his poetry. The Life and Death of Jason, the themes and remoteness of which reflect his emotional isolation, appeared in 1867, and the four parts of The Earthly Paradise were published between 1868 and 1870. In 1868, too, Morris began to study Icelandic with Eirikr Magnusson, and in the following year, collaborating with Magnusson, he published his first translations from the Icelandic, The Saga of Gunnlaug Worm-tongue and The Story of Grettir the Strong.

1870 saw the publication of Morris's prose translation of the Volsunga Saga, The Story of the Volsungs. In the 1870s, too, Morris would make a new commitment — to increasingly radical political activity — which would dominate the rest of his life, though in some ways it was only an extension of his belief that things were not as they should be; a concerted attempt to resolve the enormous disparity between things as they were and as he believed they could and should be. For Morris, the Socialist movement, after 1870, came more and more to seem to be the only way to resolve the problems — poverty, unemployment, the death of art, the growing gap between the upper and lower Classes — which he saw as being the pervasive legacy, in Victorian society, of the ongoing Industrial Revolution.

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

Textiles And Wallpapers By William Morris

William Morris Wallpaper Designs

William Morris: British Avant-Garde Designer And Advocate Of New Aesthetic Ideals

No comments:

Post a Comment